Ali Awais Amin

Control system integration is fundamental to industrial

automation. Automation professionals with even a rudimentary knowledge of

system integration realize and understand that isolation is coming to an end. In

fact, control system integrators provide maximum value to the client by

designing the system called for by the project parameters rather than having to

tailor a particular proprietary system according to the specific requirements.

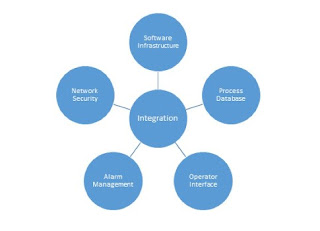

There are five factors involved in integrating different control

systems:

- Software infrastructure

- Process databases

- Operator interface

- Alarm management

- Network security.

Each has a vital role to play. Here is an in-depth look at each

one:

1. Software infrastructure: A modern automation system needs more than just configuration and

monitoring functions. Applications also must be integrated, which is why

software infrastructure is important for system integration. In an open

software architecture employing a client-server scheme, the client application

displays data from a server application.

Developed by the OPC Foundation, the OLE for process

control-unified architecture (OPC-UA) technology is designed to provide simpler

browsing and real-time and historical data exchange. OPC-UA provides

integrators more flexibility to integrate different systems in a desired

configuration instead of being locked into a specific setup by proprietary

technology. The standard's focus is interoperability and is designed to connect

many devices to create a bridge from legacy products to new devices.

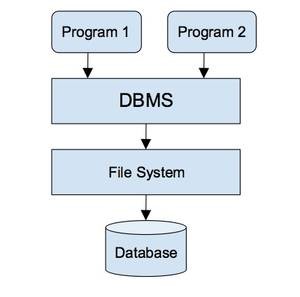

2. Process database: Database components primarily include three main components: one

or more tables for the data, a query language (e.g., SQL), and forms for

displaying or entering data. Additional components include customized page

views of data and reporting tools. Moreover, a relational database is a

collection of data items. These data items are organized as a set of formally

described tables from which data can be accessed in many ways without the need

to reorganize the database tables.

A database management system (DBMS) collects interrelated files

and programs, which allow users to access and modify files. This is an

efficient way to modify, store, and retrieve information. A query language such

as SQL is used to interact with DBMS.

3. Human-machine interface: The human-machine interface (HMI) allows operators to monitor the

state of a control process and issue commands to change the control objective.

In emergency situations, it can also be used to manually override automatic

controls. The primary aspects of HMI configuration are graphics, historical

trend, alarms, reports, and scripts. These capabilities may either be merged

into a single software application or made available as individual components

in a suite.

4. Alarm management: Alarms mark the boundary between normal and abnormal conditions

in the process and serve as the primary means of alerting operators of abnormal

situations in their facilities. Plant operation requires alarms to be

prioritized, relevant, and timely to be effective. Alarm management is critical

when integrating different control systems and so alarm systems need to be

designed to help identify critical issues.

5. Network security: Integrated control and safety systems (ICSS) operate within a

complex environment with organizations increasingly sharing information between

business systems and industrial systems. In addition to this, industrial

systems, which include process control systems, safety systems, and

programmable logic controllers (PLCs) have relied on commercial, off-the-shelf

(COTS) technologies such as Ethernet, TCP/IP and Microsoft Windows for critical

and noncritical functions. However, the isolation from the outside world is

significantly less. In fact, in an event of security breach, the potential loss

of life or production, environmental damage, and compromise to operational

safety are far more serious consequences than loss of trade secrets.

These may have ramifications beyond the targeted organization and

may also damage the infrastructure of the host region or nation.

A detailed cybersecurity analysis and cyber risk assessment

are required. They should include detailed specifications, policies

and procedures for OS patch management, antivirus implementation, and backup

and restore procedures.

Automation does not merely comprise of equipment control. It

includes higher levels of control that manage personnel, materials, and

equipment across all factory production areas. This usually is accomplished

using the documented procedures and software collectively known as the

manufacturing execution system (MES) layer. MES is a control system for managing

and monitoring important tasks in a plant. It supports the planning and control

all the way to finished product, which brings transparency to the highly

complex production tasks.

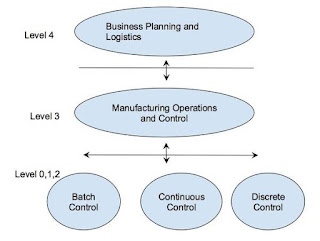

Four categories of enterprise and control systems are defined by

the ISA-95 depending on their roles. These categories are organized in a

hierarchical model in which activities associated to each category are

specified. The image below illustrates the ISA-95 Functional Hierarchy Model.

Level 0 defines the actual

physical processes.

Level 1 defines the activities

involved in sensing and manipulating the physical processes.

Level 2 defines the activities

of monitoring and controlling the physical processes. These systems are

typically implemented on PLCs and distributed control systems (DCSs).

Level 3 activities are usually

automated using MES, which also acts as the interface layer between the

control layer (Level 2) and the enterprise resource planning (ERP) layer (Level

4).

.png)